Where is the Palestinian Mandela?

On victim-blaming and who gets to make peace

I heard it again in a conversation this week, as I have heard it so many times before: ‘If only the Palestinians had a Mandela, peace would have prevailed by now.’

The idea that there is some inherent deficit in the Palestinian character that renders them incapable of producing a great leader, is an old orientalist trope. If Palestinians had a Mandela, there would be a reasonable person on the other end of the table for Israelis and the West to deal with. If Palestinians had a Mandela, they would be able to stop themselves from being bombed.

This is exactly the kind of victim-blaming rhetoric that has always served as a pretext for genocide. Before you kill a people, you must first dehumanise them. The search for the elusive Palestinian Mandela is predicated on the idea that like other Arabs, Palestinians are inherently violent. Violence is in their blood, in their souls, in their culture and peace can never be brokered with such a people.

The Mandela who is invoked in these moments is an invention of the West; he is a man who only exists as part of the racial imaginary. This Mandela is conjured as a counterweight to the savagery of Arabs, weaponised as a finger-wagging moral example to revolutionaries who are too radical. This false Mandela stands as an example of the ‘good native.’

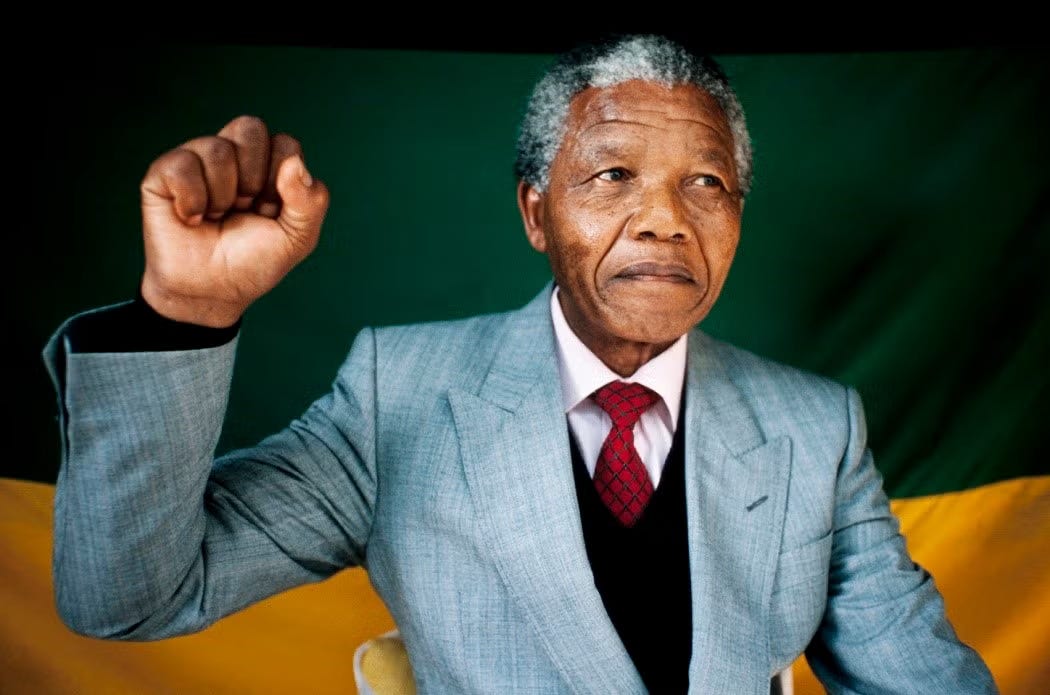

Yet the Mandela who lived and breathed has nothing to do with this mythical creation who is wished upon Palestinians. The real Nelson Mandela began his activism in the tradition of radical non-violence, running the Defiance Campaign in the1950s and using his skills as a lawyer to help mobilise thousands of people to protest segregation and pass laws. In 1960, sixty-seven people were killed in the Sharpeville Massacre, when peaceful protesters who were members of the Pan Africanist Congress were gunned down by apartheid police. Later that year, Mandela concluded that taking up arms was unavoidable. He founded the miliary wing of the African National Congress. My father, who was a young man at the time, was an early recruit.

When he was found guilty of treason in 1964, Mandela refused to denounce violence. He said, “I do not, however, deny that I planned sabotage. I did not plan it in a spirit of recklessness, nor because I have any love of violence. I planned it as a result of a calm and sober assessment of the political situation that had arisen after many years of tyranny, exploitation, and oppression of my people by the Whites.”

When Mandela emerged from prison twenty-seven years later to negotiate an end to apartheid, he did not apologise for any aspect of the ANC’s fight for freedom.

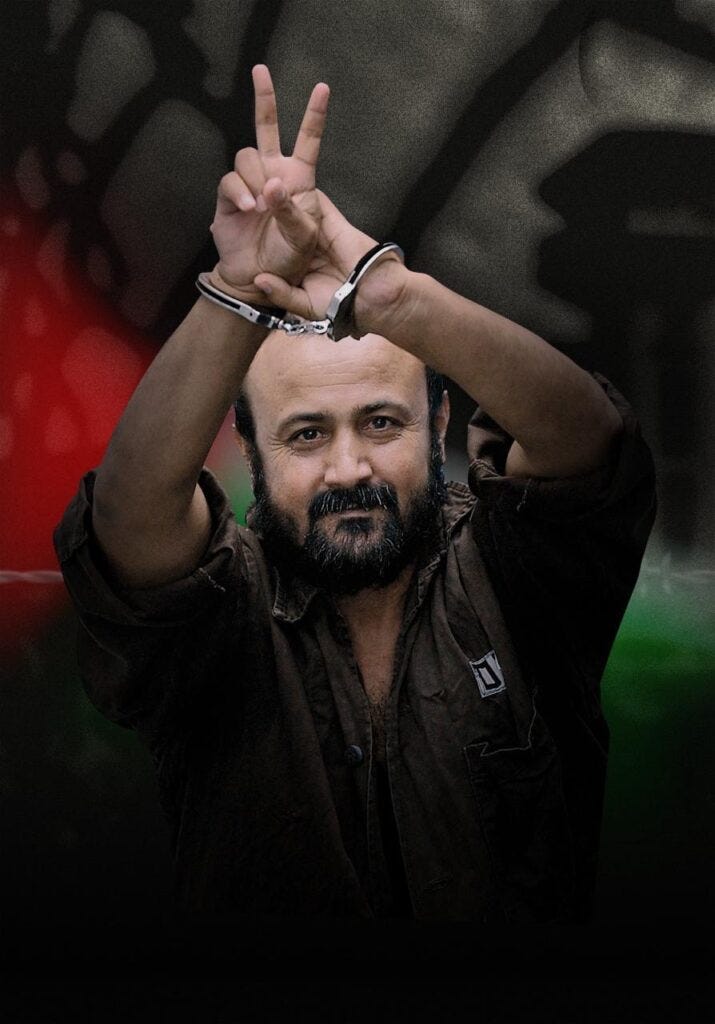

In the same vein, the popular Palestinian leader, Marwan Bargouti, who has been locked up for thirty years has said, “The occupation is negotiating with us while maintaining its occupation; therefore, we want to negotiate while maintaining resistance. You can’t have occupation and peace at the same time.” Margouti has proven time and again that he is prepared to reason with Israel, based on respect and genuine engagement.

If the Western world was serious about peace, it would have forced the Israelis to release Bargouti, and the many Palestinian leaders who remain in Israeli prisons. But the US-Israeli plan that has stopped the bombs for now, has nothing to do with a genuine process of peace and self-determination for Palestinians.

Even if Bargouti did not exist, there are many others worthy of being called heroes. There are countless Palestinians who know what it will take to forge a society founded on peace rather than hate. We have all watched the maturation of a generation of Palestinian youth who have been shaped by checkpoints, forced resettlements, Israeli snipers and bombardment. Their steadfastness in the face of these attacks has been overwhelming. We have also seen the courage of Palestinian journalists who have demonstrated time and again what it means to love the truth and to fight for it to be told. There is no shortage of Mandelas or Bargoutis in Palestine.

What is missing of course is leadership on the other side. In an article published last year, Barghouti’s brother Muqbel quoted Marwan as saying, “We Palestinians have our ‘Mandela.’ We are waiting for an Israeli de Klerk.”

The leadership on the Palestinian side is not the problem in this equation.

The First Invention of Mandela

The invention of Mandela pre-dates the Western hijacking of his name and reputation. The invention of Mandela began during the long hard years of apartheid when South Africans in the liberation movement began to understand that the world needed a single hero to rally around.

We chose Mandela. It was a deliberate decision. We understood the ways of the Western mind. A single figure. A heroic man. He was a worthy icon: tall and handsome; eloquent and fearless.

Every campaign carried his name. When he sang, his name hung above our heads, rising with the weight of our voices. The apartheid regime banned his image, but we kept him alive in the world’s imagination. The university students in the UK and America who marched for South African to be sanctioned in the 1980s kept his name and image alive. The shop workers at the Dunnes stores in Ireland who refused to handle South African goods and said no to unloading grapefruits and oranges grown on stolen lands -- they too kept Mandela in their hearts.

The more we loved him, the more the regime in Pretoria feared him. He was not the terrorist they proclaimed him to be, though of course he made no apologies for carrying a gun in defence of his humanity. They feared him because they could not kill him. The promise of white supremacy is that white life matters more than Black life and so, any Black person who is perceived as threatening can be eliminated. This was true for everyone except Mandela. Because at a certain point it became clear to the Afrikaners in power that killing Mandela would be costly.

If they killed the hero, he would become a martyr, and they would lose the West. And if they lost the West, there would be no reason to survive. The architects of apartheid had tied themselves to the West economically, ideologically, and culturally. If the West pulled away from the supremacist project at the tip of the African continent, if it refused to accept the passports of white South Africans, and denied them the capacity to invest in their stock exchanges or benefit from their investments, the entire enterprise would fall apart.

The regime knew that the Europeans and the Americans were happy to do business with them despite the protests and objections of their citizens, but they also understood that the political calculus would change if they killed Mandela.

Mandela understood this too. This understanding that he was too famous to die strengthened his hand and allowed him more room to be brave.

Barghouti has no such leeway; no Palestinian does, not Shireen Abu-Akleh, not Anas Al-Sharif, not Hossam Shabat, not a single one of the hundreds of journalists killed during the genocide. Every time the Israelis kill another prominent Palestinian journalist, it becomes clearer that we are in uncharted territory and there is no activist handbook for this moment.

The South African regime - as egregious as it was - had red lines. The genocidal state that has unashamedly live-streamed its war crimes does not.

Of Prizes and Protest

In October 1984, Bishop Desmond Tutu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The prize meant something then, but those days are long over. In his speech, Tutu reminded the audience listening to him speak, that at that stage three million Black South Africans had been uprooted from their homes and “dumped” in the Bantustans.

He went on, “I say dumped advisedly: only things or rubbish is dumped, not human beings. Apartheid has, however, ensured that God’s children, just because they are black, should be treated as if they were things, and not as of infinite value as being created in the image of God.”

He went on to note that apartheid’s dumping grounds, “are far from where work and food can be procured easily. Children starve, suffer from the often irreversible consequences of malnutrition – this happens to them not accidentally, but by deliberate Government policy. They starve in a land that could be the breadbasket of Africa, a land that normally is a net exporter of food.”

It’s hard to read this and not burn with the shame and the rage of what we have witnessed for the last few years in Gaza.

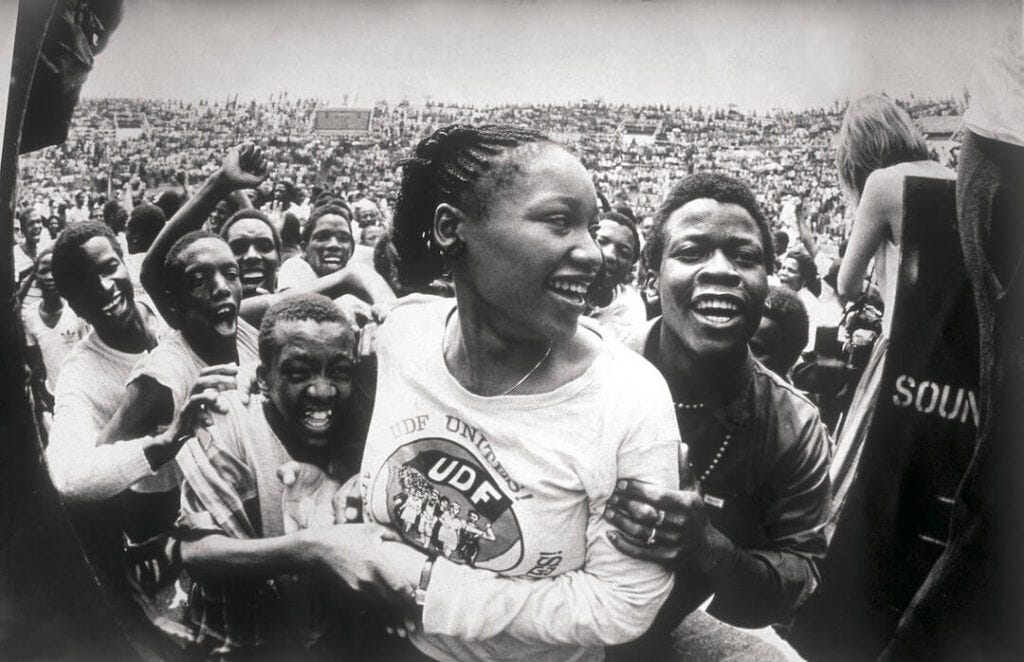

A few months after the archbishop accepted his prize, a rally was held to honour him in Soweto. Thousands were gathered as a Zindzi Mandela took to the stage that day. The sixteen-year-old daughter of Winnie and Nelson Mandela was the last person to address the crowd. Her father remained on Robben Island, but he had managed to smuggle out a letter and had asked his child to read it to the residents of Soweto.

The letter was written in response to a statement made by President Pik Botha in Parliament a few weeks earlier. The apartheid leader had offered to release Mandela if he ‘unconditionally rejected violence as a political weapon’. It was the sixth offer of its kind. Previous versions had offered Mandela exile in exchange for his personal freedom.

Mandela’s response was fiery and clear, and it remains one on my favourite pieces of text. Addressing his people directly, Mandela wrote:

I cherish my own freedom dearly, but I care even more for your freedom. Too many have died since I went to prison. Too many have suffered for the love of freedom. I owe it to their widows, to their orphans, to their mothers and to their fathers who have grieved and wept for them. Not only I have suffered during these long, lonely, wasted years. I am not less life-loving than you are. But I cannot sell my birthright, nor am I prepared to sell the birthright of the people to be free. I am in prison as the representative of the people and of your organisation, the African National Congress, which was banned.

What freedom am I being offered while the organisation of the people remains banned? What freedom am I being offered when I may be arrested on a pass offence? What freedom am I being offered to live my life as a family with my dear wife who remains in banishment in Brandfort? What freedom am I being offered when I must ask for permission to live in an urban area? What freedom am I being offered when I need a stamp in my pass to seek work? What freedom am I being offered when my very South African citizenship is not respected?

Only free men can negotiate. Prisoners cannot enter into contracts.

Mandela’s words were a reminder that we chose well; that he was indeed worthy of being entrusted with the responsibility of speaking on our behalf, of carrying our hopes on his shoulders from that faraway place where he was locked away.

A decade later Mandela would win the Nobel Peace Prize. He had to share it with Frederik De Klerk, who was the last apartheid president of South Africa. It was not lost on many of us that a Black man who had fought for freedom, spent twenty-seven years in one of the harshest prisons in the world, and then come out to negotiate the world’s most ambitious young democracy had to share a peace prize with a man who had dedicated his life to an ideology of white supremacy before finally capitulating to international pressure by entering into negotiations to end apartheid.

A few days before the joint prize was announced, the white South African army raided a “suspected black terrorist hideout” and killed five people. The ‘terrorists’ were five unarmed Black teenagers.

De Klerk accepted the prize with the same hands that had signed off on the boys’ murder. Mandela accepted the award in the interests of the delicate peace he and his comrades were stitching together.

At moments like this I find it helpful to remember that the hypocrisies of this time are no different to those that have gone before. Alfred Nobel invented dynamite long before he founded the prizes for which he is most remembered. Warmongers have always detonated bombs while speaking of peace. The champions of liberalism have long gestured towards concord while hosting the purveyors of war. Trump and Netanyahu and of the now but they are not new.

And so we know in some ways, how to meet this moment. We know that we can emulate the posture of those in whose lineage we follow. We can only meet each day with what we have. On some days I am weary. On others I have clarity and energy, but always, I have love. As Fred Moten says the task is to be, “with other people, working, dancing, suffering, some irreducible convergence of all three.”

In the end this is all we have; the togetherness and doing-ness that have always pushed us closer to freedom.

This lucid historical comparison is essential reading for those who never knew these stories, as well as those whose memories are fading and muddled Please share widely. Thank you, Sisonke..

This is brilliant and much needed, Sisonke. Thank you for teaching us this history.